WHAT IS THE SECRET TO TCHAIKOVSKY'S "PATHÉTIQUE" SYMPHONY?

THERE IS A FAMOUS PHRASE: DEATH IS A CAREER MOVE. TCHAIKOVSKY INTENDED TO CREATE A WORK THAT WOULD CROWN HIS ARTISTIC CAREER BEFORE HE DIED. BUT IT HAD A SECRET. WHAT? READ ON.

THIS POST IS ONLY FOR CALLING ALL CONDUCTORS SUBSCRIBERS, INVITED TO JOIN ME FOR A FREE CMO GREAT MAESTROS REPERTOIRE MASTERCLASS DISCUSSING TCHAIKOVSKY’S PATHÉTIQUE SYMPHONY ON JUNE 14 AT 12 EST / 18 CET. HERE IS THE ZOOM LINK TO JOIN IN. FOR THOSE WHO READ MUSIC, HAVE YOUR SCORE READY:

John Axelrod is inviting you to a scheduled Zoom meeting.

Topic: CMO GREAT MAESTROS FREE JOHN AXELROD TCHAIKOVSKY 6 “PATHÉTIQUE" MASTERCLASS

Time: Jun 14, 2024 06:00 PM Zurich

Join Zoom Meeting

https://us02web.zoom.us/j/82342488859?pwd=QU8yMkJ1aWlOR29EUGdlaXA5ME1uZz09

Meeting ID: 823 4248 8859

Passcode: 632191

Find your local number: https://us02web.zoom.us/u/kuw3uXl4F

TCHAIKOVSKY’S PATHÉTIQUE: AN ANSWER TO THE SECRET?

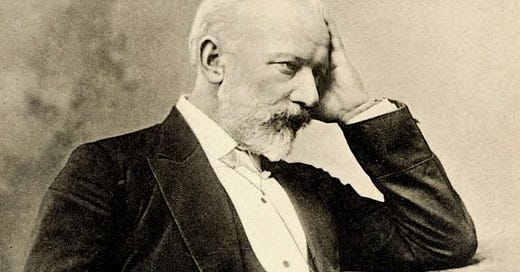

In 1889—only a year after completing his Fifth Symphony—Tchaikovsky wrote to his friend, the Grand Duke Konstantin Romanov, that “I want terribly to write a somewhat grandiose symphony, which would crown my artistic career… For some time I have carried in my head an outline plan for such a symphony… I hope that I shall not die without carrying out this intention.” Tchaikovsky seems to have begun sketching this ambitious project in 1891, and by April 1892, he wrote to the pianist Alexander Ziloti that “I am already thinking of a new large composition, that is, of a symphony with a secret program.” A version of the “outline plan” found among Tchaikovsky’s sketches for his next symphony after the fateful 5th has a rather different trajectory:

The ultimate essence of the symphony is Life. First movement—all passion, confidence, thirst for life. Must be short (finale death—result of collapse). Second movement—love; the third—disappointment; the fourth ends dying away (also short)

However, this plan, for 1892 was a Symphony in E flat, that remained incomplete. It was reconstructed and edited by Bogatyryev and became Tchaikovsky’s unofficial Symphony #7. And the finale was not at all funereal or dying away.

He abandoned the work (which later also was included in an incomplete piano concerto 3), and instead focused on a new version in 1893 of the symphony to follow his Life theme.

That became what we know as the Pathétique, Symphony #6.

He wrote to his nephew: Vladimir “Bob” Davydov:

“During my journey I had the idea for another symphony, this time with a programme, but such a programme that will remain an enigma to everyone—let them guess; the symphony shall be entitled: A Programme Symphony (No. 6); Symphonie à Programme (No. 6); Programm-Symphonie (No. 6). The programme itself will be suffused with subjectivity, and not infrequently during my travels, while composing it in my head, I wept a great deal. Upon my return I sat down to write the sketches, and the work went so furiously and quickly that in less than four days the first movement was completely ready, and the remaining movements already clearly outlined in my head. The third movement is already half-done. The form of this symphony will have much that is new, and amongst other things, the finale will not be a noisy allegro, but on the contrary, a long drawn-out adagio. You can’t imagine how blissful I feel in the conviction that my time is not yet passed, and that to work is still possible.”

That is the genesis and evolution of the work. Now what about the secret?

To the Grand Duke and patron, Konstantin Romanov, Tchaikovsky added:

“Without exaggeration, I have put my whole soul into this symphony, and I hope that Your Highness will approve of it. I don’t know whether the symphony is original in terms of its musical material, but as far as its form is concerned, it does display an original feature in that its finale is written in adagio tempo, rather than allegro, as is normally the case.”

Is this the finale that ends by “dying away” as described in the note from his sketches? Its marking of “Adagio lamentoso” (Slow and lamenting) and subdued ending would seem to confirm this conjecture. Furthermore, in the weeks before the premiere, the poet Aleksey Apukhtin (Tchaikovsky’s lifelong friend and former schoolmate) passed away. Konstantin Romanov wrote to Tchaikovsky, suggesting that he compose a musical setting of Apukhtin’s poem “Requiem.” as an homage, but Tchaikovsky hesitated:

“I am somewhat worried by the fact that my latest symphony, which I have recently completed and which is due to be performed on 16 October (I should awfully like Your Highness to hear it), is suffused by a mood very close to that which pervades [Apukhtin’s ] Requiem. I think that I have made a good job of this symphony, and I am afraid of repeating myself if I were right now to embark on a composition which has an affinity with its predecessor in terms of spirit and character”.

After thoroughly studying the poem, he added in another letter that “indeed my last symphony (especially the finale) is suffused by a similar mood.”

Tchaikovsky conducted the new symphony himself at the premiere, which took place in St. Petersburg in October 1893. Interestingly, the work was presented simply as Tchaikovsky’s “Symphony No. 6,” without a subtitle. For whatever reason, the symphony seems to have been coolly received by the audience. Tchaikovsky wrote, “Something strange is happening with this symphony! It’s not that it displeased, but it has caused some bewilderment.” Nevertheless, he continued to believe that it was his best work.

But was this the secret? A Requiem for his friend?

Let us examine Tchaikovsky’s death and learn.

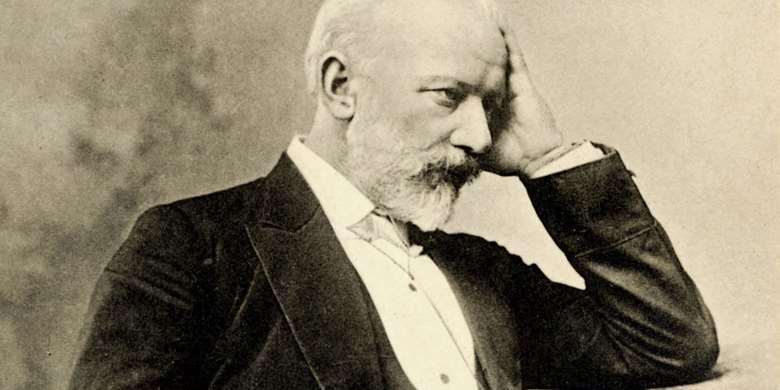

Medical records suggest that Tchaikovsky died of cholera after drinking unboiled water. The Czar gave him a state funeral. And the 6th Symphony, after its premiere which was not totally successful, became the final and universally embraced statement of Russia’s greatest composer and has remained since his greatest musical achievement.

But did he die of cholera, or was he, as some serious students of Tchaikovsky now contend, forced to commit suicide by a ''court of honor'' made up of his former classmates at the College of Law in St. Petersburg? The composer may have acted out of fear that he and especially his family would be disgraced if the fact of his homosexuality was made public. The Czar already knew, and Tolstoy, Tchaikovsky's idol, might learn of it any day. So runs the argument for suicide.

The British musicologist David Brown flatly states: ''That he committed suicide cannot be doubted, but what precipitated this suicide has not been conclusively established.'' Mr. Brown goes on to say that the composer ''almost certainly died of arsenic poisoning. The story that he died of cholera from drinking unboiled water is a fabrication.'' If Mr. Brown is right, the official story of Tchaikovsky's death can only have been a classic coverup, a conspiracy involving his brother Modeste, doctors and others close to the composer in his final days. Modeste, himself a homosexual, may have had a special interest in keeping his brother's secret.

Whatever the climate of acceptance may have been in certain clandestine circles, it is indisputably so that homosexuality in his time was a criminal offense. The actual wording of the criminal code of the Russian Empire, as published in 1842, 1866 and 1885 reads: The punishment for homosexuality was lashing with birch rods, deportation to Siberia and loss of all civil rights. No wonder Tchaikovsky, at age 37, tried marriage (he left his bride after nine days), and in letters to Modeste urged his brother to take a similar step in hopes of protecting the family name. It does not take a tremendous leap of imagination to conceive of such a tortured man committing suicide to keep the truth from coming out.

And yet, would this idea have manifest into the mood of the work? Clearly the theme of Life, with a fading away is not necessarily contingent upon suicidal tendencies. And Cholera was quick. He would not have proposed his own self-requiem if dying from Cholera. There was another reason. And I may have an answer.

His homosexuality is indeed a key to understanding. Tchaikovsky struggles with his sexuality throughout his life, with a failed marriage and many letters attesting to his unhappiness. He even considered it something that could be cured. Was it suicide? In the end, it was not. However rumors persist that Tchaikovsky took the poison on orders from his old classmates, who had convened a hasty ''court of honor'' after learning of his liaison with a nephew of Duke Stenbock-Thurmor. The Duke had written a letter of protest to the Czar, bringing the ongoing matter of Tchaikovsky's sexual proclivities to the point of official scandal.

Therefore, whether suicide or cholera, was Tchaikovsky aware of this inevitable fate and composed his own requiem in advance? Or was it more a philosophical, psychological, even literary portrait of his own inner suffering? I find this more plausible as composers are auto-biographical in their musical paraphrasing. Think of Berlioz’ Fantastique or Schumann’s 4th Symphony or Dvorak’s New World or Strauss’ Tod und Verklärung and so on.

We can look to Tchaikovsky’s own Fatum, from 1868. Tchaikovsky originally wrote this tone poem to his own very abstract program dealing with the cruelty of fate in people's destinies. Tchaikovsky himself was not satisfied with the outcome--indeed he destroyed the orchestral score, which was reconstructed from a set of parts after he died. While there are some musical similarities with the Symphony #6, and a wonderful C minor allegro “Fate” melody, perhaps Beethovenian in style, giving it an admirable impression, but it is not the main source for his Pathétique nor its secret meaning.

What then might have given Tchaikovsky an inspiration? One of the playwrights whose works Tchaikovsky greatly admired was Shakespeare, who during Tchaikovsky’s lifetime had rapidly risen to the position of being among the most performed writers on the Russian stage: In 1830, the critic Pletnev had asked, in his Thoughts on Macbeth, “why read other writers when [Shakespeare] contains them all?”, and when Pushkin wrote his Little Tragedies he had openly adopted Shakespeare as his model. But it was the performance of Hamlet given by the great actor Pavel Mochalov in Moscow in 1837 which was the decisive event in establishing Shakespeare on the Russian stage. In the 19th century, until the 1840s, Russian art had been lost, aimlessly trying to base itself on French models, or on Walter Scott, but “when the true unadulterated, unmutilated Shakespeare was shown in Russia by Mochalov,” wrote the Russian-American critic Isaac Don Levine, “spiritual Russia, as if at the touch of a giant magic wand, awakened.” The critic Belinsky noted that “since Mochalov, Russians understand that there is but one dramatic poet in the world and that is Shakespeare.”

We know from Romero and Juliet that Tchaikovsky was fascinated by unrequited love and impossible loves and romantic love that ends with death. The Fantasy Overture, in its final version, has become the highest ideal of passionate romantic Russian music. In The Tempest, Tchaikovsky summons up the magic island and the marine world in ravishing orchestral colours, while the lovers’ music, tender and restrained – almost chaste – rises to heights of amorous intensity beyond anything to be found in the play. Hamlet, fifteen years later, equally derives from 19th-century views of the play – in this case, as a cosmic statement about human nature. Tchaikovsky’s brother Modeste suggested the play, but the program was Tchaikovsky’s own, drawing from him a massively impressive portrait of a Romantic outsider, a Byron, or, indeed, a Pechorin (from Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time) or an Onegin. The character of Hamlet himself had acquired, since Mochalov’s trailblazing performance, a particular resonance for Russians: the indecisiveness, the sense of doom, the constant introspection seemed to them to express the very essence of the Russian soul. As it happens, Tchaikovsky also wrote a very serviceable score for a production of Hamlet in St Petersburg some years later.

In fact, the Hamlet Overture, which was very popular in Tchaikovsky’s lifetime, has some remarkable similarities to the Pathetique.

So Shakespeare, and Hamlet, in particular, had an indelible impact on his imagination. And if we combine this influence with his own insurmountable personal tragedies of living as a gay man, and an impossible love for which he was exposed, might it be clear that Hamlet could have once again captured his consciousness and dictated these musical ideas of the symphony and the outcome of that final adagio that “dying away?”

Already in the opening of the 1st movement, we feel the same tragic mood of Hamlet. The opening mournful bassoon line is typical of funeral music since the Baroque. The opening passage with its descending chromaticism is most deeply expressed in the upbeat to m. 5 in the violas, m. 11, with more anguish in m. 13 and again with the upbeat to the ritenuto in m. 17 before the fermata and close of the introduction.

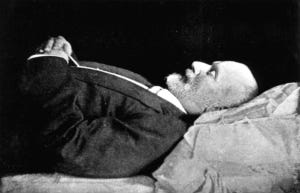

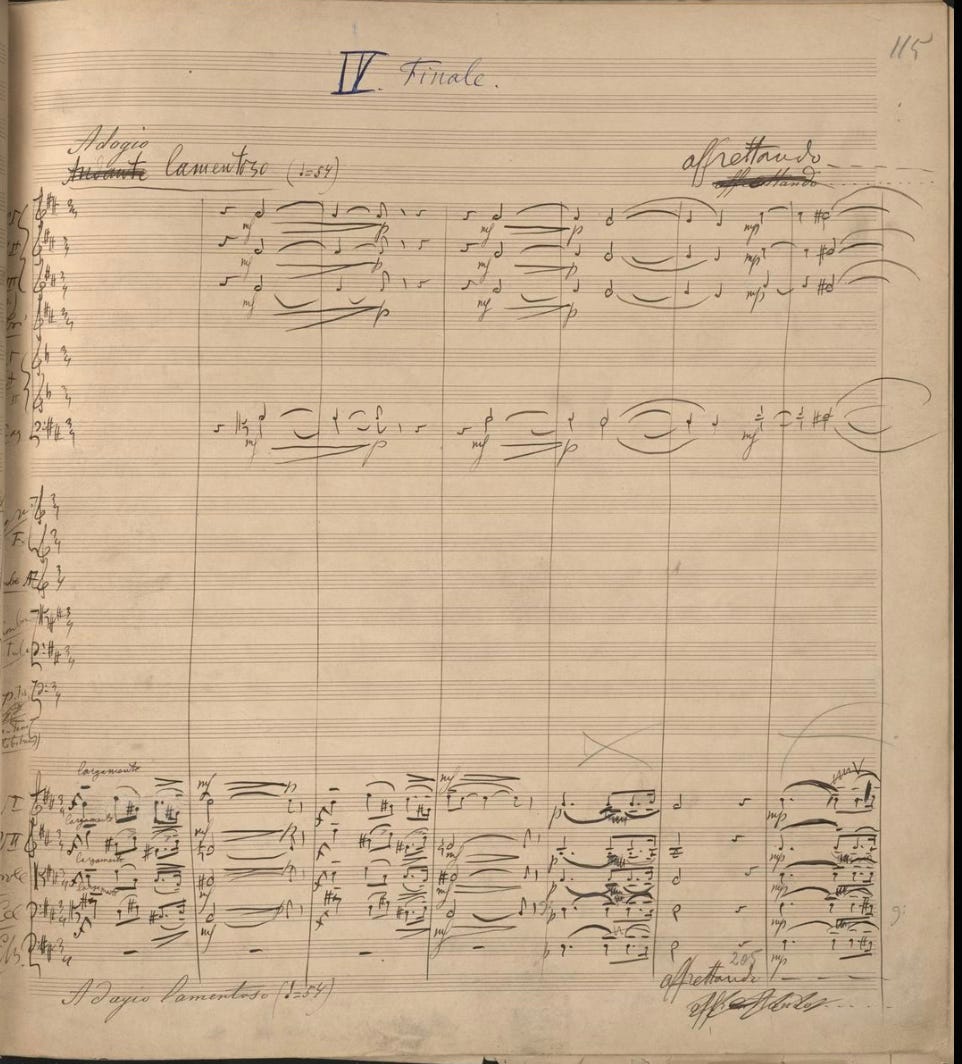

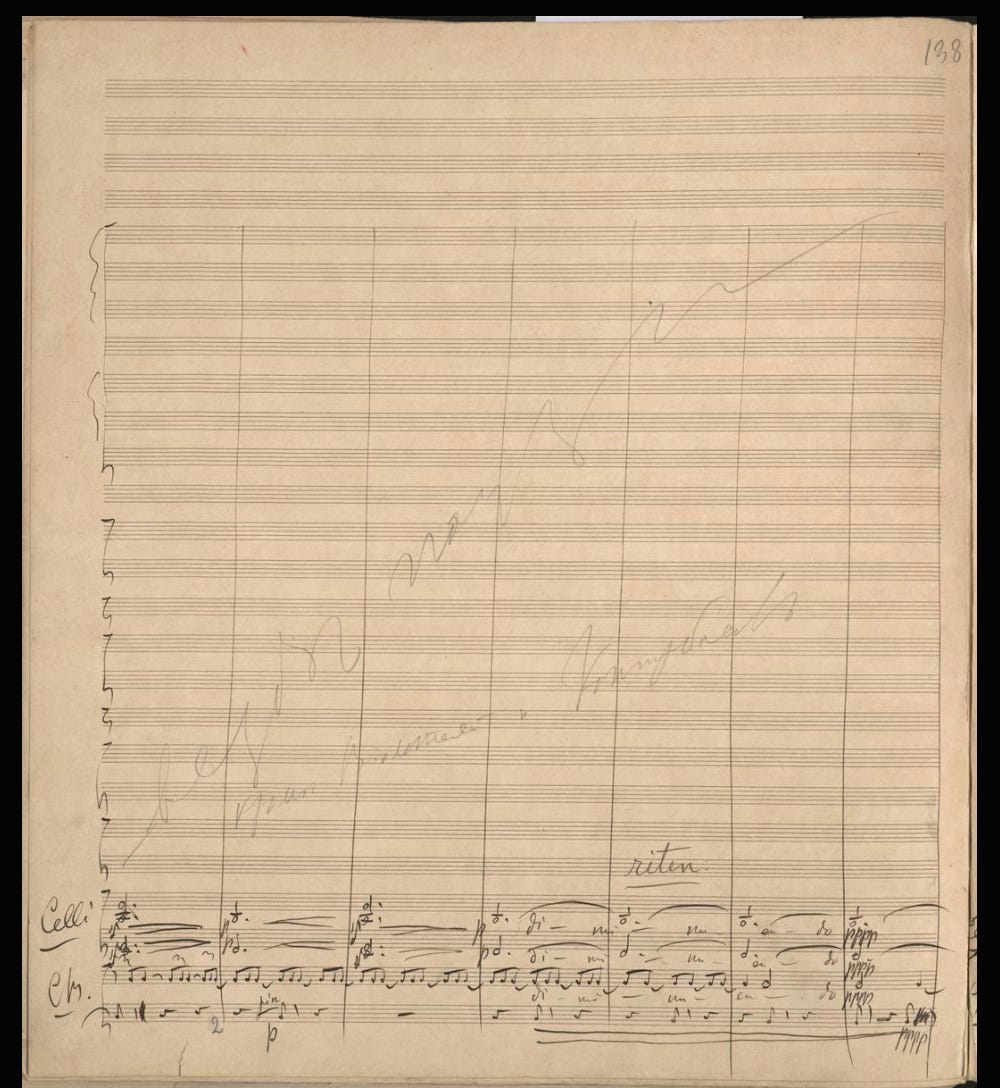

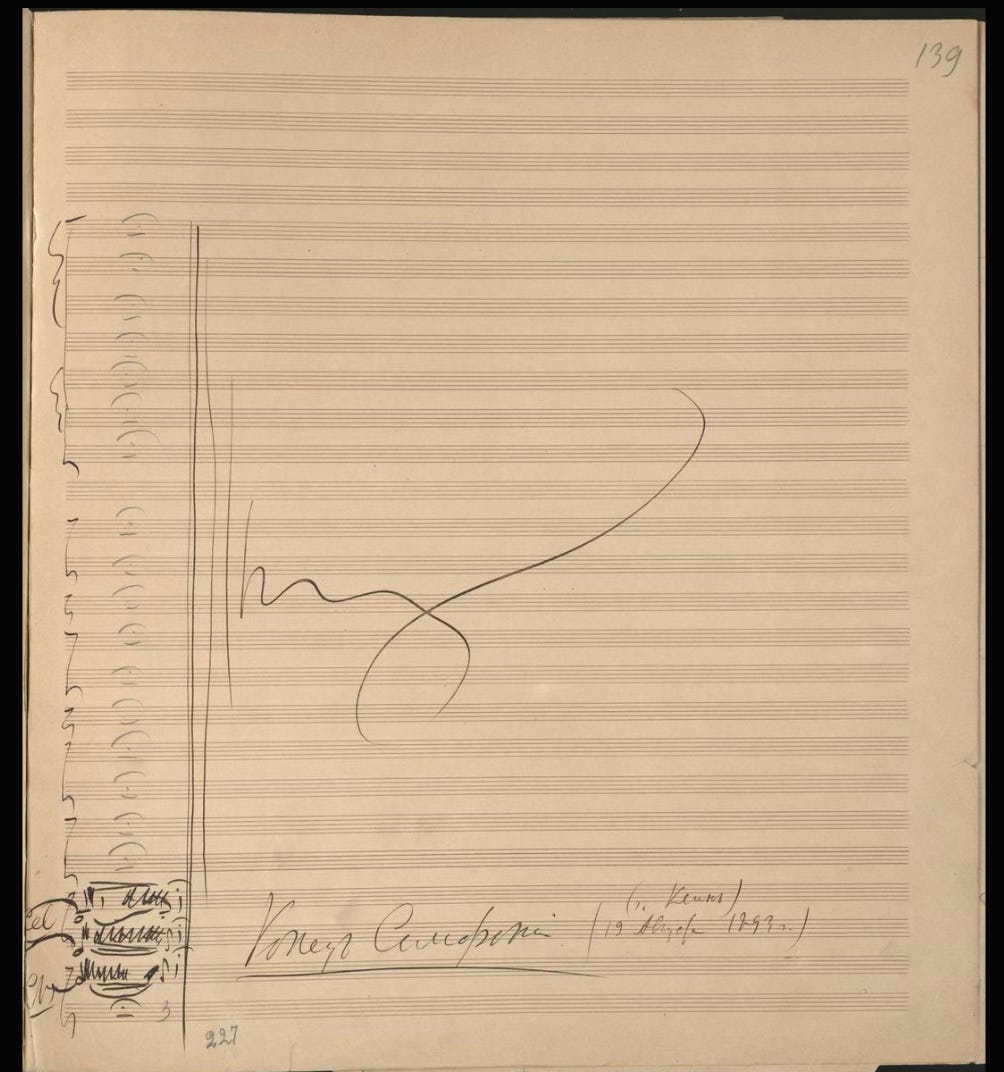

*Original manuscript pages from the Russian National Archive:

https://www.culture.ru/catalog/tchaikovsky/ru/item/archiv/simfoniya-no-6-pateticheskaya-2017-08-17

Suddenly the allegro non troppo begins with the violas having to take care with their intonation., but it is the celli that need a clear entrance on the 4th beat of 28 leading into the exceptional 2/4 measure before letter A and the upbeat of the same tragic motive heard in the bassoon and violas in the 1st violins, but this time with more agitation, leading to a high held note in expressive in measure 38.

As the strings start the saltando, don’t ignore the legato phrasing of the wind melodies. After letter B, give a crescendo for the bassoon to the high G# and makes sure the horns do not drag the espressivo hair pin.

With the un poco animando in m. 67, the brass fanfare moves forward after the 3rd beat, taking care to make the quarter notes tenuto in phrasing. Give a good entrance for the timpani at m. 70 on beat 3. This third beat becomes important in the un poco piu animato to letter D and following for the trombones in m. 81 and 82. The ritardando molto should be rehearsed and observed with a cantabile cello melody, allowing time to slow from triplets to duplets before the violas, with great care in intonation once again remind us of that earlier anguish before the fermata.

But it is the famous andante melody that helps us understand the anguish and reminds us of another impossible love: That of Don José for Carmen. This melody, starting in m. 89 and repeating throughout the movement, bears a striking resemblance to Don José’s “Flower Song” from Bizet’s Carmen (one of Tchaikovsky’s favorite operas). Both melodies begin with a falling, triadic line, and when the melody leaps up to a descending scale, it recalls the phrase when Don José sings “Car tu n’avais eu qu’à paraître,/Qu’à jeter un regard sur moi,/Pour t’emparer de tout mon être” (“For you had only to appear,/Only to cast a glance at me,/To take hold of all my being”). Tchaikovsky marks this part “incalzando”—which can mean “urging” or “pressing.”

Careful of the upbeat to the moderato mosso. The 1/8 note equals the following 1/4. The winds should speak as actors do, with character and meaning. At m. 105 do not ignore the trombones and trumpets with the ascending and descending tenuto quarter notes. At issue is always the septuplet before E and after. Is it a crescendo or a diminuendo. The difficulty of the intonation has led to a diminution of the phrase but it also has musical logic. Note at m. 121, the saltando evolves to a tragic tenuto alla corde and a final fortissimo before the winds remind us of the viola adagio melody of the introduction. The suffering increases.

Our andante melody (with a generous triplet upbeat for all to play the triplet pesante and non staccato), becomes even more passionate. The moderato needs a good cue for the 2nd violins to double the 1sts. The clarinet and bassoon phrase the two note slurs. And finally, the clarinet gives us our melody like a fading memory. Note the first time at adagio mosso, the 8th note upbeat and the echo has a 16th note updates. The question of the bass clarinet substituting for the bassoon on the 4 descending 8th notes in fermata is most likely due to the limitations of bassoon players at the time. Today, most bassoon players will play it. Best not to conduct but to let the bassoon solo simply play the notes slowly.

Then the explosion. How to prepare this alarm clock for the audience? Sustain the silence, but give a clear neutral 1-2 before a ff upbeat to generate such force. The celli and basses play off the string sextuplets. The upper strings play from the string, not lifting the bow so much after the tied note to connect the phrase. Ask for more weight in the index finger of the bow.

At letter H we have a similar musical fugue heard in Romeo and Juliet, that most exemplary of impossible loves. Ask the violas to play on one string, “sul do.” The upbeat to m. 190 is like a cannon blast, but the trumpet needs a clear downbeat and the sound should be above the rest of the orchestra if possible, Russian style. At m. 201, we hear later a quotation of the Russian Orthodox chant in the trombones: “With thy saints, O Christ, give peace to the soul of thy servant,” a traditional prayer for the dead. Tchaikovsky already anticipates his demise.

At letter L, don’t rush and allow a beautiful sound, but phrase the strings across the bar lines, following the brass quarter notes. A clear cue for the horns at m.223 is important to prepare them for what is to come at letter M, a foreshadow of the finale, but with more hyperventilation. The strings are sul tasto and in shadow for the opening tragic motive. Note the upbeat in this exciting passage at m. 249 is only forte, then fortissimo with 253. The upbeat to 263 after a huge crescendo requires the military trumpets in triplets to be above the orchestra again. Finally, Passion with a capital P at letter P is heard in the 2nd beat with pesante brass and timpani, with bells up in m. 269. In 270, it is recommended to follow the revisions in the score for the timpani to make a crescendo, rather than diminuendo.

In fact, what is most striking is the use of the timpani after the Romeo and Juliet syncopations before letter Q. While the original draft has a diminuendo leading to the climax, most conductors demand a crescendo to lead dramatically into this pleading, screaming section, but only in forte.

Many bow changes are needed from letter Q, remaining in a beat of 2 half notes. The tension builds in m. 284, beating in 4 with the timpani crescendo. The trombones are sustained in this slower tempo in 4. The final FFF chord 3 after R is the resolution, with the timpani following the pizzicati in the celli and bassi like nails in the coffin.

After a long, exhausting fermata, give a clear downbeat on 1 to the celli and bassi for the arco entrance and we return to the andante melody like a nostalgic but unfulfilled memory of love. The ritenuto with the horns in m. 315 to the 3rd beat is the denouement. The subdivided upbeat of the winds to the andante mosso should be clear, the 1/8 note of the preceding adagio becomes the 1/4 note. The pizzicati are in tempo but deep, heavy and dry. From the chest, like the myagkiy znak soft sign in Russian pronunciation. Give an early entrance to the trumpets of the funeral band, but remind them to not get too loud in the hairpin. At m. 350, the trombones need a cue, allowing the celli and bassi to slow down and accompany the last 1/8 notes of the trombones final chord. The ending of the movement with the timpani is a prescient foreshadow of the final adagio, the bass pizzicato, not like nails, but instead the throwing of dirt onto a grave.

Reminiscent of the composer’s ballet music, the 2nd movement theme would seem to be a waltz, except that it is in 5/4 rather than the usual three-quarter time. Some commentators have poetically suggested that this is a waltz “missing a beat,” but while its meter is unusual, the melody sounds utterly complete as it is. What is most important is the internal triplet, meant to slow down the crescendo and to allow an eloquent graceful turn. The idea of the 5/4 becomes more like a souvenir, a memory of good times past, a life that had some happy moments, although overshadowed by the complexity of the unpredictable and impossibility of love. Best to rehearse and conduct the celli, with a 2+1+2 gesture, the triplet being a circular upbeat to the two quarter notes leading to the next measure. When taking the repeat, allow the celli to play and you simply accompany the eighth notes in a round 3 pattern. m. 17 and 21 are often played with a portamento in the strings between the 1st and 2nd quarter notes, also in 112 & 116. The winds do not make the glissando at letter A, however. It is advised in m. 33 (and m. 127) to conduct in 5 to ensure the pizzicati in strings are together after between 3, and to stay in 5 until the arco melody returns, at which a 1/4 + dotted 1/4 fluid gesture allows for a luxurious and generous sound.

The trio acts like a yearning, a “sehnsucht,” with an internal sigh from the 2nd and violas to compliment the repeated hairpin melody of the violins and celli. Once the woodwinds take the theme, the pizzicati are less like ballerina toes, fluttering to the music, but instead running away from the fate of not being able to live the love desired.

The return to the main theme at letter H comes with a logical and traditional ritardando and diminuendo, rather than the printed crescendo.

At letter M, articulate the horns but not separate. m. 148/149 need a bit of panache conducting in 5 to be precise. Letter N is like a church chorale in the winds and brass.

Stay in tempo to allow the accented dotted half note to not drag. At letter O, the wind soli are expressive, full of individual character, arriving to the clarinet and 1st violins reminding us of a reflection of the waltz theme and trio theme. An even further imposed rallentando allows the final almost arpeggiated pizzicato and chord as if saying farewell.

The 3rd movement, a march, is always received by the public as if the finale, with an enormous applause to follow. But the march has a different meaning. Not unlike the march to battle, it is instead another reference to an impossible love: the Marche au Supplice from Berlioz’s Fantastique, his own symphonic fantasy of loss of love and the inevitable hallucinatory march to the guillotine. All the downward scales are like a vortex of energy drowning our musical hero.

Start in 2 to have the Vivace tempo. It is not only fast. It is vivacious. Pay attention to the violas at the end of m. 2 and the contrast in winds between triplets and duplets. The main theme, first in the oboe then in the strings, must be continuous without breaks. The strings can play close to the string across the bar line, without releasing the bow, as was done in the 1st movement. m. 117 is important to give a clear ictus on beat 2 for a secco pizzicati in the strings. The same for m. 155.

M. 35 (and 174) for pizzicati and the piccolo entrance in 36 and 175 are important. Lead the piccolo with direction in the crescendo, and the same for the staccato trombone that follows.

The upbeat to 45 and 446 after letter E (and the parallel after letter S) are not references to Beethoven 5 by accident. Fate plays an important part in much of Tchaikovsky’s music, and we are given this motive as an example, in the way Brahms did the same. The knocking on the door is also reinforced by the Forte Marcato string melody. Is the note E flat by coincidence here, coming from his earlier E flat symphony, or perhaps a reference to the E flat “Eroica,” a nod to his motherland Russia in defeating Napoleon?

Accented winds from letter G are like church bells in crescendo. The clarinet and bassoon in duplets are heard without much dininuendo leading into the main march at letter H. After the fanfare at letter K, the downbows, played au talon, need to be shown this by gesture. The winds echo the violas from measure 2 and the long hairpins in the winds and bassi are expanded to include brass, and even tuba in the recapitulation after letter BB.

After letter T, and the brass played fortissimo, the timpani also has a crescendo to the 2nd beat of m. 194, and. along diminuendo, leading a clear entrance of the celli in misurato and the bassoons in pianissimo. The march motive is exchanged among sections (pay attention to the 2nd violin entrance at . 203), and give a clear forte downbeat to the triplets of the bassi at letter V. Horns are then played above the orchestra and the trombones and horns and strings are sustained in crescendo, from m. 214.

At letter X, the Gran Cassa (Bass Drum) comes in with a book and the scales of the strings and winds are played like a whip to the 2nd beat. Letter Y is played A Tempo with the half notes held long. Give good cues for the cymbals who finally play with an even greater crash at letter Z. At letter DD, don’t let the bass drum be too loud in its tremolo. It fills the space with the timpani to create an earthquake with the brass fanfare until the famous moment at EE. Conduct in 4, slowing down for a giant cymbal crash on beat 4 and continue in a Maestoso March, (as was done in Soviet Times), almost half tempo of the primo tempo. The march remains in 4 from m. 283 until m. 289, with the upbeat being a half note and the music returning to a tempo in 2.

Take care not to be too loud with trumpets at letter HH, but allow a poco a poco crescendo until the FFF at 312, the Gran Cassa cue at 313 and the cymbals after a strong beat 2 in m. 315. After letter II, following the ascending strings and the melodic brass. KK becomes a circular beat to maintain the tempo and energy, especially with the off beats 3 after KK. LL need short brass 1/8 notes, played secco; however, the descending brass from m. 338 should not be too staccato but instead with phrasing, still in 2, until the final punctuated chords, in a beat of 4, from m. 341. At last, the whole note chord, returns to a beat of 2 half notes and the last triplet, after a strong 2nd beat release is a final reminder of Beethoven and the force of destiny. Audiences agree with a predictable eruption of applause.

The emotional finale is played attacca, without pausing from the preceding movement, ostensibly to down out the clapping of the public, but more likely as an emotional outpouring a deep sadness, with the melody intertwined between 1sts and 2nds, like two bodies unable to separate, and more likely an internal dialogue within Tchaikovsky. The gay man versus the noble composer in society. Two world separated, two personalities in conflict. How ingenious of the composer to include his own internal drama inside the dialogue of strings!

It is important to note that Adagio is an afterthought. While it is important to know that this symphony is particular in that it is the only one that Tchaikovsky gave metronome markings, the Finale was originally Andante Lamentoso, 1/4 note = 54. However, to start too fast would not contrast the important Andante at 76 that follows.

Therefore, interrupt the inevitable applause after the 3rd movement and start with a big breath and conduct in 6 to show that dialogue and to make sure the tenuto 16th note is pronounced. Then in a slow Adagio 3. The phrasing between beats of 6 and 3 are predominant until the affrettando, hastening in 3 towards the rallentando after letter A. The phrasing of the tenuto winds, emphasizing the internal hemiola, is heavy. Finally, where printed Andante at 69, the winds allow for a subdivision to articulate the appoggiatura, until the end of the phrase.

Then, at the Adagio poco meno che prima, a clear neutral downbeat must be given. Then a subdivision of the 2nd beat to allow for all strings to enter, leading to a repeat of the 6 pattern and 3 pattern alternation. After letter B, the bassoons are in 3. The ponderous pesante rhythm of the à2 bassoons are in 3 until m. 34, when the 16th notes are subdivided. M. 35 must show the 2nd horn clearly each beat until the end of the phrase with. cutoff on the 8th note after beat 3. The 8th note rest is often held like a fermata before the following triplets in Andante.

This is the walk down the colonnade. The horn needs a clear breath with a triplet upbeat to get the correct tempo and maintain it over the tied notes. Violins are marked “con lenezza e devozione” (“Lenezza,” interestingly, is not a standard Italian word. Some believe it is a misspelling of “lentezza”—“slowness”—although others have suggested that it might be an obscure, literary variant of “lenità”—“soothing.” “Devozione” means “devotion” or “piety,” carrying a religious connotation).

The melody is one of surrender, resignation, acceptance. Careful to not rush the animando. Let it all flow naturally. In a paraphrase of Dylan Thomas: We do not go quickly into that good night.

Pull back to Tempo 1 of the Andante to build more tension. At m. 54, the ritenuto of the trumpets must be sustained to return the horns into the andante tempo and the violins are more expressive. They too make a huge sustained ritenuto before letter E. Stretch the melody even more until finally, the animando leads to letter F. This piu mosso is the last chance for Tchaikovsky to scream: “Why Me?!* Hold the 8th notes then go forward with the triplets until finally, the stringent articulates the descending hemiola in triplets from m 77, through vivace until the final beats slap in your face. Hold the fermata frozen.

Give an upbeat on the 3rd beat of m. 82. another upbeat at 84 more exhausted. After the fermata of 86, give the 3rd beat for the upbeat and cut off after a full quarter note. the same for 88. Upbeat on 3 to 89, give the down beat, and as before, subdivide after beat 2 leading into G. But this time, the Andante non tanto, is in 3. Lead the horns after m. 97. It is advised to have all horns play, not only 2 and 4 from m. 98 in order to hear them well, cutting them off one before H after the 3rd beat in subdivision as this cutoff should be in the tempo of the incalzaldo of the following measure, with the downbeat of letter H, already in the tempo of the 8th note subdivision, but this time the 3rd beat is a full quarter note upbeat to the fortissimo, continuing in tempo. At 5 before H, start in 3, piano dolce, and continue to increase the crescendo and the passion in the stringendo molto, with once again, the hemiola starting at m. 112 on 1st beat, then 3rd, then 2nd in the next measure, then again 1st and 3rd in m. 114 until the 2nd beat of the FFF in 115 at moderato assai, with the string in misurato, then tremolo on letter I, then misurato from beat 2 in 117, then tremolo in 118, and so on, increasing the tempo through the incalzaldo, until, as advised, the upbeat to one before K as 1/2 string misurato, the other 1/2 tremolo to create both intensity and articulation in the ritenuto.

Letter K we arrive at Hamlet’s shuffling off “the mortal coil.” The horns are gestopf, brassy and metallic in their FF accents. With each 3rd beat string upbeat, the tempo is held back, and finally, at m. 133,, the strings, like Tchaikovsky himself, are exhausted in temperament. The 2nd beat low horn, as always, stays is this nasal, snarly sound, in FF until the printed diminuendo, but still present, always, as the body casts off its exoskeleton. The Tam Tam at letter L is the final judgement. The trombones are a funeral chorale, the instrument symbolic of spiritual piety. Lower and lower, the tuba is given on beat 3. The final chords are 4 and 5 ppppp. The epilogue begins: Here lies Piotr Tchaikovsky.

Alas, the secret of the symphony now becomes clear: Modern horns, invented in 1839, have rotary valves and piston valves, initially aimed to overcome problems associated with changing crooks during a performance. These coiled rotary valves are heard with a metallic sforzando, hands deep in the bell, “gestopft” creating a unique character consistent with Hamlet’s quote: “Devoutly to be wish'd. To die, to sleep; To sleep, perchance to dream—For in that sleep of death what dreams may come, When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, Must give us pause, there's the respect, That makes calamity of so long life.”

There is a precedent for this. The Tam Tam and the same stuffed Sfz horns are used in the Hamlet overture. The valves resemble a coil, just as a snake would shuffle off its skin. So too might Tchaikovsky have wished to shuffle off the stain of his sexuality. The coil, a metaphor for skin, would be to rid oneself of an affliction, and dreamily die, free of suffering. Therein likes the secret. Hamlet was the inspiration.

The bassi are steadfast, the sound of inevitability with heartbeat triplets that do not stop until the end. The outpouring of strings, again in dialogue, are this time the cries of all who mourn their hero. Once again, the Sfz in the bouché horns from 152, with the clarinets, the soulful instrument from the 1st movement, are the last vestiges of life. Two last breaths in Sfz in the celli before the curtain falls. And the finally syncopated rhythms, with pizzicato and a long held B minor, are the final breaths before the silence. The soil is thrown on the mortal coil. As the final line says: “If it be now, 'tis not to come: if it be not to come, it will be now: if it be not now, yet it will come: the readiness is all. The rest is silence. Goodnight, sweet prince, And flights of angels sing thee to thy rest!”

The last page has only one last measure. The original folio has empty pages that follow. That, in my opinion, is the meaning of the symphony. The rest is silence.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Calling All Conductors Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.